Unable to destroy a surrounded American battalion without food, water, medical supplies, and almost out of ammunition, one story reportedly had a German leader referring to them as, “American gangsters.” The unconfirmed quote was later used in a movie.

Even if not said, it wouldn’t have been far from wrong in describing how the Americans of “The Lost Battalion” fought.

The Germans knew, from captured members of the battalion, that they were fighting against mostly immigrants to America, raised in the poorest sections of metropolitan New York. They were tough and hard and already used to fighting for survival – sometimes against each other, living in the roughest ethnically divided neighborhoods of New York City.

The Americans held their ground for 5 days, refusing to surrender, often fighting in brutal hand to hand combat against a superior force attacking from every side, at least once with flame-throwers. They also lost 30 men to friendly artillery fire that fell on top of them, instead of the enemy.

Of the nearly 600 men who entered the Argonne Forest, only 194 were able to walk out.

One company from New York’s 307th Infantry Regiment, attached to the battalion, but not caught in the encirclement, also fought for those 5 days to reach their comrades and rescue them. They succeeded, allowing the rest of the American and French armies to fortify and expand the path they created in the center of the German Army.

The World War was over just 5 weeks later.

Part of their story is part of my heritage, which is why I took an interest in seeing West Easton’s WWI plaque recognizing our WWI Veterans, moved to a place of prominence among their Brother In Arms – those who fought in WWII.

Today, I was given the privilege of addressing those in attendance at the Memorial Day Remembrance and focused on WWI and immigrants, hoping to convey some of the importance in remembering WWI Veterans and the contributions immigrants have given our country by defending it.

Prejudice and fear today, is not unlike it was then. It’s just focused on a different group of people.

Below is what I had to say.

It may be I was given this opportunity to speak because I introduced a resolution to Council in May of 2017, that a change be made to the location of the WWI plaque. With the approval of 3 other Councilmen, the resolution passed with a majority vote.

Some may ask, “Why did I introduce a resolution drawing attention to a plaque dedicated to 55 men in a war none of us recall first hand and of no blood relation to me?” I am not a life-long resident of West Easton and this is a war that ended 100 years ago, this coming November 11th.

To answer that question requires some brief history.

You will see here today, the names of 55 men who served in WWI, or as it was referred to at the time, “The World War.” The plaque was a gift from William J. Flynn in 1929. Mr. Flynn was the Safety First Volunteer Fire Company’s first President in 1912 and proprietor of The Spring Grove Hotel. A tall obelisk dedicated to WWI veterans once stood where the larger monument exists today. Our larger monument was created after our nation’s victory in WWII and remembers those men who served in that world war.

Post-WWII was a time of great pride in winning a war that saw sacrifices from not only the men and women who served in the armed forces, but a public who rationed and worked to support the war effort. The United States of America had become a super-power.

Prosperity and growth occurred. Recognition of WWII veterans was a priority and in communities throughout the country, monuments, statues, and plaques dedicated to WWI veterans were moved to make room for the newest heroes, or the building boom that came with the baby boom.

Here in West Easton, the WWI obelisk was broken up and used in the foundation of the larger monument that would hold the WWII plaque. The WWI plaque was placed on the back of it.

The change made to Spring Street, which once ran behind where the large monument now stands, now turns toward 7th Street, below the monument, eliminating vehicle and foot traffic behind it. Hedges were later planted on either side and behind the large monument offering no enticement to investigate its back face.

55 West Easton residents who served in WWI had become, unintentionally, hidden in plain sight.

I only became aware of the plaque a few years ago.

As an “immigrant” to West Easton, I did some research in order to understand how these men found their way to the back of the large monument.

I lived in the borough for two years before discovering the brass plaque was actually a dedication to WWI veterans. I had assumed the plaque I had seen from a distance was a common-place tribute to the governing body that were in office when the large monument was erected – a plaque similar to those often found on buildings and other structures elected officials often feel is deserving of self-recognition.

One day, I finally wandered closer, curious to see the names of those patting themselves on the back. It was disheartening to me, not only as a veteran myself, but as the grandson of a WWI veteran, to see 55 men relegated to obscurity on the back side of the large monument. As a peace-time veteran, I felt an obligation to these men who served before me, as these men served in a time of war that saw more than 116,000 Americans die. Their service to country and community should not remain, “hidden in plain sight.”

I thought about my WWI veteran grandfather who arrived from Italy, without his parents at the age of 11. It was a time in our nation’s history when Italians were cartoon caricatures in major newspapers, depicted with features and costumes of hairy organ grinder monkeys, or as dark and drooling organ grinders themselves, lecherously looking at high-society women.

Despite his challenges in the years that followed, from an existing population upset at the large influx of Europeans, who they believed would steal jobs and rape women, he didn’t hesitate to serve his new country that was calling on men to fight in Europe.

He soon found himself on the front lines, a member of the newly formed New York’s 307th Infantry Regiment, largely made up of recently arrived immigrants living in poverty.

It was these immigrants who were the first to break through the German lines, reaching “The Lost Battalion,” a battalion who had been surrounded in the Argonne Forest for 5 days, losing two-thirds of the men to casualties from friendly artillery and enemy infantry attacks, but refused to surrender, despite the lack of food, water, or supplies. The Lost Battalion was also largely constituted of immigrants, with 54 different native languages or dialects spoken.

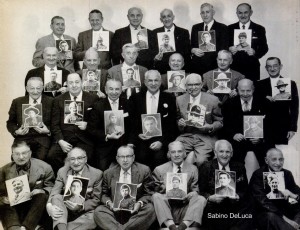

My grandfather and about two dozen men from his Company, still living in 1959, were finally recognized for the breakthrough and rescue, appearing in Life Magazine’s February issue that year. They were pictured proudly holding their individual military portraits from when they were young men.

As a young boy, I would inquire of my grandfather about Italy. Occasionally, I would mistakenly refer to him as an Italian. He always made a point to correct me. “I am an American. Italy is not my country. I just happened to be born there.” That was confusing to me as a boy, as he said it with a thick Italian accent he never lost.

He refused to refer to himself with the hyphenated version, “Italian-American.” For him, he was only an American and proudly displayed the proof he was awarded only a few years after arriving at Ellis Island. Framed and under glass, his certificate of citizenship hung on the wall of his living room for any visitor to see, should they mistake his Italian accent for him being anything other than American. He and men like him are those I associate with WWI veterans.

Looking at some of the names on this plaque, I wonder how many of them might have arrived to the United States from a foreign country, when they answered the call to take up arms to defend freedom and democracy. If not them, it may have been their parents. Clyde Stout, whose name is among these men, is an example.

Clyde is the grandfather of our life-long resident, Nancy Stout, in attendance today. Clyde’s father immigrated from Germany and despite the anti-German sentiment the war produced, Clyde’s father saw him off to war, because Clyde’s father was an American, who happened to be born in Germany.

Nancy, by the way, told me just yesterday she was unaware the plaque on which her grandfather’s name appears, had been on the back of the large monument.

It was my grandfather and other war veterans I spoke with in my youth that convinced me serving in the military was a duty to country, if called upon to do so.

Our young men and women serving now are volunteers. Those who volunteer during our current world situation of multiple conflicts, ensure what many of us hope will remain a safe and free country.

Freedoms provided to all of us, and for those from other countries seeking a better life, as my grandfather found here, despite the existing prejudices at the time he arrived.

Our freedoms, especially The Freedom of Speech and Freedom of The Press are among those our military ensures no foreign power or radical belief will take away from us. Such freedoms, despite what may be anyone’s personal dislike of our free press reporting factual news, or non-violent expressions of free speech by citizens, should never be under threat of reprisal from our own government.

While our more recent military conflicts are at the forefront of our thoughts, we must, as a nation and within our own community, never forget those who served in time of war or conflict, always providing our permanent forms of tributes to them a place of prominence.

Thanks to those serving on Council last year, Mr. DePaul, Mr. James, and Mr. Mammana, their support of the Resolution to move the plaque has allowed our community to once again, provide a place of prominence for these 55 West Easton residents who served in WWI.

This newest monument and the re-dedication remembers these men who have long since passed. Every veteran from WWI is now gone and it rests upon us, not to forget their generation’s sacrifice.

Disclaimer: On January 4, 2016, the owner of WestEastonPA.com began serving on the West Easton Council following an election. Postings and all content found on this website are the opinions of Matthew A. Dees and may not necessarily represent the opinion of the governing body for The Borough of West Easton.